Water History of Payahuunadü

The Owens Valley Indian Water Commission (OVIWC) has an excellent StoryMap of the Indigenous history of waters and lands of this valley.

We suggest you start there.

After that, read on for an overview of the water history that informs our work.

Getting Oriented

Payahuunadü, also known as Owens Valley, California, sits on the western edge of the Great Basin. The Great Basin region of the United States consists of over a hundred different basins and ranges. The Great Basin is also the largest region in North America where water does not drain into the ocean. Instead, the water in these basins evaporates, fills up groundwater tables, or flows into lakes.¹

Map of the Great Basin. Payahuunadü runs along the western edge.

Two mountain ranges, soaring to a height of over 14,000 feet, border Payahuunadü: the Sierra Nevada to the west and the Inyo Mountains and White Mountains to the east. Each year, snowmelt from the east side of the Sierra flows down into Payahuunadü, which translates to “land of flowing waters” in the Nüümü language. The streams and creeks naturally feed the Owens River, which flows southward into Patsiata (Owens Lake), the lake at the valley’s southern end. These waters also percolate into the soil to fill the water table that cradles the valley from below.

¹The Great Basin; The Great Basin and the Basin and Range; Great Basin Shrub Steppe

Paya: Nüümü word for “water”

Nüümü peoples have cared for the lands and waters of Payahuunadü for thousands of years. They dug irrigation ditches that spread the snowmelt across the valley and encouraged staple foods like taboose and nahavita to thrive. Each year, Nüümü bands elected a person to serve as tuvaijü, who would evaluate the needs of the land and oversee the painstaking process of digging and managing miles of irrigation ditches. They built dams to flood alternating sections of land, which allowed areas to rest and facilitated fishing from the recently-redirected channels. Spreading the water with these methods also kept the groundwater tables high. Overall, these water practices helped the valley’s plant life flourish and supported healthy local hydrology.²

Map drawn by surveyor A.M. Von Schmidt in 1855-1856, describing how Nüümü peoples irrigated their lands.

Harry Williams, Bishop Paiute Tribe Elder and Water Protector, studied these irrigation ditches for much of his life. He learned how to read the land and identify where the ditches had been. With help from students and volunteers, he mapped at least sixty of them using GPS. As he put it: “The entire valley was our garden. Our ancient ditches made the groundwater rise. As we spread the water, our gardens grew.”³

² Teri Red Owl, Payahǖǖnadǖ Water Story, Wading Through the Past: Infrastructure, Indigeneity & the Western Water Archives, Ed. Char Miller, 2021, Claremont Colleges Library, Claremont.

³ Honoring A Water Warrior: How Harry Williams Fought for Paiute Water Rights in Owens Valley; How the Owens Valley Paiute Made The Desert Bloom

Settler Water

Settlers slowly trickled into the valley starting in the 1850s. Their farming and ranching techniques began to alter the ecology of the valley, which also disrupted Nüümü food sources. Tensions built and eventually escalated into warfare over the land and waters of Payahuunadü in the early 1860s. In July 1863, US soldiers forced Nüümü men, women, and children to march from Payahuunadü to Fort Tejon, over 200 miles away. It is a testament to the deep ties between Nüümü people and their homeland that most who survived eventually made their way back to the valley. Soldiers also massacred Nüümü people in Patsiata, the lake that was – and for many, still is – so central to life in the valley. By the late 1860s, outright violence had diminished and settlers controlled the valley. Many Nüümü people began working as laborers on farms and ranches.

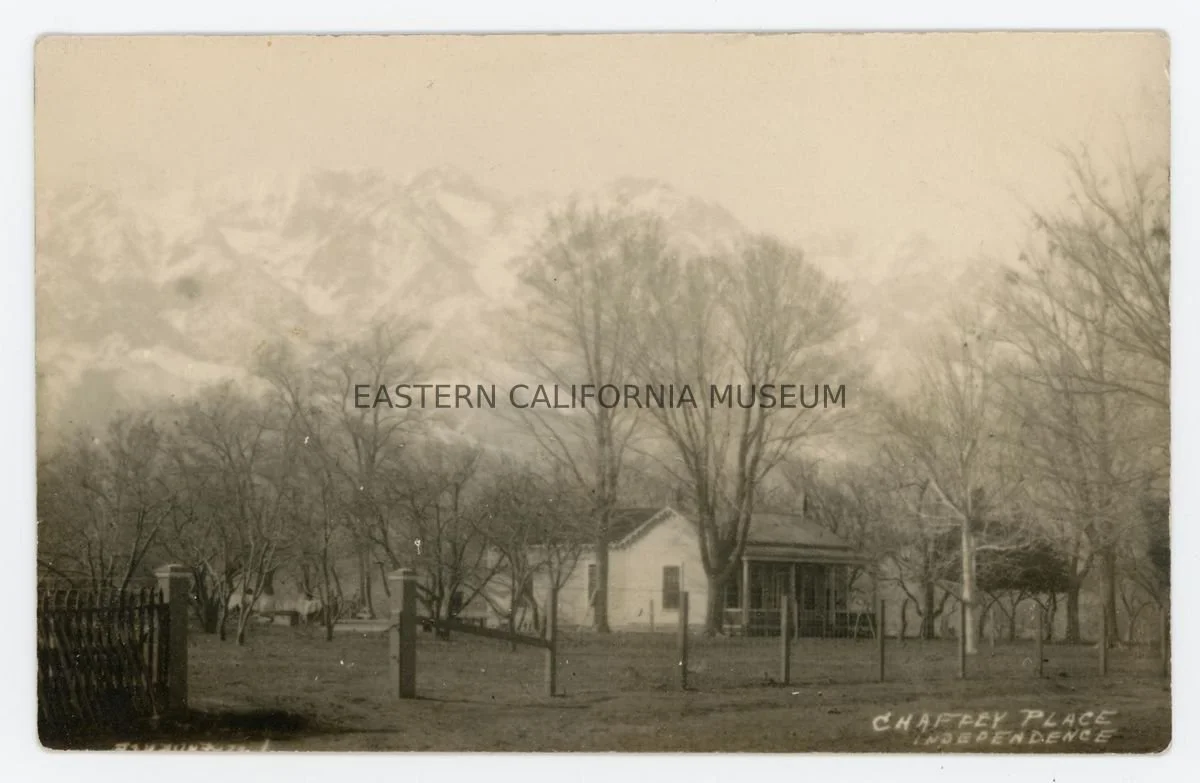

A ranch near Independence, circa 1908.

Over the next fifty years, more settlers moved to the valley and began building their own ties to its lands and waters. Most likely making use of remaining Nüümü irrigation ditches, settlers also dug an extensive network of ditches to spread water for their farms and ranches. Most settlers set up farms on small plots growing a variety of different crops, while others set up more extensive ranching operations. They employed the system of water rights that continues to dominate the U.S. West to this day. This included “appropriative rights,” which means that they ordered residents’ water rights in a priority ranking based on when each person had started diverting water from a given waterbody.⁴ This principle, also known as “first in time, first in right” raises interesting questions about water rights in Payahuunadü. After all, the Nüümü people were the first to divert and move water from countless waterways throughout the valley.

⁴ Gary Libecap, Owens Valley Revisited: A Reassessment of the West’s First Great Water Transfer (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), 9-10.

Los Angeles Aqueduct

Los Angeles entered the scene in 1905, when the people of Los Angeles passed a bond measure to pay for the building of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) completed the aqueduct in 1913, and started diverting water immediately. The furor of the California ‘Water Wars’ exploded in the 1920s, when LADWP began buying valley lands for their accompanying water rights. Farmers mounted protests like occupying the Alabama Gates spillway in 1924. LADWP paid many farmers what was considered then a fair price for their lands. However, land values plummeted for the farmers whose property LADWP refused to buy. Many settlers left the valley, which resulted in many Native folks losing their jobs on farms and ranches as well.

Farmers and other settlers seized the Alabama Gates aqueduct spillway and temporarily released water back into the dry Owens River channel, 1924.

Over the next few decades, LADWP continued to expand its reach in Payahuunadü. They built infrastructure extensions to take water from further north in Mono County. For example, they completed Long Valley Dam in 1941, creating Crowley Lake, the largest reservoir in the aqueduct system. LADWP also worked with the federal government to develop the 1939 Land Exchange of Native lands. The federal government gave 2,913.5 acres of Indigenous lands to LADWP (who use the water rights that go with these lands). In return, LADWP gave 1,391.48 acres of city-owned lands to the tribes (without the water rights). This land came in the form of three small reservations in Lone Pine, Big Pine, and Bishop. LADWP did not resolve the tribes’ water rights in this exchange, and they remain unresolved to this day.

Another principle of western water rights is “use it or lose it.” LADWP had claimed far more water throughout the Eastern Sierra than it was actually exporting. To avoid losing their rights to this water, LADWP completed the Second L.A. Aqueduct in 1970. In dry years, they could not entirely fill the new aqueduct with surface water, so they ramped up groundwater pumping. Pumping in the 1970s dramatically lowered groundwater tables, dried up springs and killed many groundwater-dependent plants.⁷

Note the spikes of groundwater pumping after the Second LA Aqueduct was built and before the Long Term Water Agreement.

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) passed in 1970, the same year that the Second L.A. Aqueduct was completed. It quickly became one of the best legal tools for protecting the environment, and the County of Inyo, where Owens Valley is located, put it to use. CEQA required LADWP to produce an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) to evaluate the impacts of its water extraction and plan for ways to mitigate environmental harm. Local advocacy groups, Inyo County officials, and ultimately the courts found the first three LADWP EIRs inadequate. They pushed LADWP to do more to address the damage caused by its intensive groundwater pumping. LADWP and Inyo County released a final EIR in 1991. The court did not accept this EIR until a settlement involving state agencies and environmental groups was reached in 1997.

By 1991, Inyo County and LADWP had agreed on a plan to guide future groundwater pumping and surface water management, the Inyo-L.A. Long Term Water Agreement (LTWA). The goals of the LTWA are to avoid causing certain decreases and changes in vegetation (as mapped in the 1980s), to not cause further significant environmental impact, to provide water for uses in Inyo County, and to provide water to Los Angeles. This agreement has guided relations between LADWP and Inyo County ever since. Among many other provisions, it places some controls on the amount of groundwater that LADWP can pump.

The LTWA controls on pumping are known as the “ON/OFF” management system, which is a means to curtail groundwater pumping if soil moisture at monitoring sites “linked” to certain LADWP pumps is found to be insufficient to support the overlying vegetation. There are 22 ON/OFF monitoring sites, linked to 50 LADWP pumping wells. Vegetation parcels are also monitored to assess species composition and cover of living vegetation and compare it with mid 1980s “baseline” conditions. This scientifically unproven“ON/OFF” system created a lot of concern when it was proposed and then adopted by LADWP and Inyo County in the 1990s. Because of its experimental nature, the public demanded an overlay known at the time as the Drought Recovery Policy. However, three decades later, it is clear that this management strategy is imprecise. It fails to take into account meaningful information such as the depth to groundwater beneath vegetation, changes in species composition, and other ecologically relevant factors. Many pumping wells are also exempt from this system.

Recent photograph from a mitigation project in the valley.

Because of significant adverse impacts to the Owens Valley environment identified in the 1991 EIR, LADWP committed to implement many mitigation projects. Several additional mitigation projects subsequently were agreed upon and adopted in a court-mediated “Memorandum of Understanding” (1997 MOU). One of the mitigation projects receiving much attention was the Lower Owens River Project (LORP), which called for re-watering the Owens River bed south of the Aqueduct intake that had been dry for 93 years. LADWP was slow to initiate most of the projects, and to this day, many are incomplete and the subject of ongoing controversy. Nevertheless, LADWP annually pumps ground water throughout the valley.

⁵ Owens Valley Indian Water Commission, “Reimagining Payahuunadü An Indigenous Water and Land History of the Eastern Sierra Nevada, California.”

⁶ Abrahm Lustgarten, “Use It or Lose It Across the west: exercising one’s right to waste water,” ProPublica, June 9, 2015.

⁷ Sophia Borgias, “Drought, settler law, and the Los Angeles Aqueduct: The shifting political ecology of water scarcity in California's eastern Sierra Nevada,” Journal of Political Ecology, Volume 31, 2024.

⁸ “CEQA Process Overview,” Governor’s Office of Planning and Research.

⁹ “Inyo/LA Long Term Water Agreement,” Inyo County Water Department.

Patsiata

Patsiata, also known as Owens Lake, showcases the extreme harm caused by water diversion and export from the Great Basin region. It also embodies a fraught hope for improvement and the halting pace of change. By 1926, Patsiata had dried up entirely, because LADWP diverted the entire Owens River and other tributaries to the lake into the L.A. Aqueduct that otherwise would flow into this terminal lake. The lakebed became the worst source of PM-10 dust pollution in the country. Vicious dust storms plagued the valley for decades. Many residents experienced respiratory health issues. In the 1970s, local residents, Inyo County officials, Native American Indian tribes, and the Great Basin Air Pollution Control District all began pushing LADWP to address the dust. LADWP delayed for years. However, in 1987, the EPA’s Clean Air Act led to deadlines to bring the region into air quality compliance.¹⁰

Dust storm on Patsiata in 2010.

In 2001, LADWP finally started implementing dust mitigation measures, such as shallow flooding, managed vegetation, and gravel. Tribal elder Kathy Jefferson Bancroft, of the Lone Pine Paiute Shoshone Reservation, has led many Nüümü and Newe peoples in supervising this work and protecting the Indigenous cultural resources in and around the lakebed. In fact, after years of work, a coalition of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers succeeded in nominating the region to the National Register of Historic Places. It is called Patsiata Tübiji Nüümü-na Awaedu Ananisudüheina, or Patsiata Historic District. On the whole, these dust control measures have reduced dust considerably. The new hybrid lakebed has also restored Patsiata as a critical stopover for migrating birds on the Pacific flyway. However, the area still does not consistently meet air quality standards.¹⁴

Walking around Patsiata as part of the spring 2024 “Walks of Resilience and Accountability” in Payahuunadü.

During the enormous runoff year in 2023, more snowmelt flooded the valley than LADWP could control. The water remembered its path to Patsiata, despite over a century of diversions. More water flowed into Patsiata than in most residents’ living memory. The lake reached a little more than 6% of its former water content (covering about 41% of its historic surface area). Most folks wanted LADWP to continue to fill the lake going forward.¹⁵ However, LADWP let this water evaporate without replacing it. In fact, they hope to reduce water usage in their dust control strategies going forward and pump the groundwater under the lake to use as dust control.¹⁶

¹⁰ Karen Piper, Left in the Dust: How Race and Politics Created a Human and Environmental Tragedy in L.A. (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006), 12-46, 191.

¹¹ See “DWP archaeologists uncover grim chapter in Owens Valley history,” L.A. Times, June 2, 2013.

¹² “State Commission Offers Overwhelming Support to Acknowledge Indigenous History at Owens Lake,” May 5, 2022.

¹³ “Important Bird Areas: New opportunities for birds at Owens Lake,” California Audubon.

¹⁴ Owens Lake Scientific Advisory Panel, Effectiveness and Impacts of Dust Control Measures for Owens Lake (Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2020), 19-20.

¹⁵ Public comments given at the Technical Group meetings and Standing Committee meetings of April and May, 2024.

¹⁶ Stipulated Judgment in the matter of the City of Los Angeles v. the California Air Resources Board et al. Superior Court of the State of California, County of Sacramento. Case No. 34-2013-80001451-CU-WM-GDS. Approved by the court on December 30, 2014. For a more recent discussion: Owens Lake Scientific Advisory Panel, Effectiveness and Impacts of Dust Control Measures for Owens Lake (Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2020), 1-12.

Image Credits:

Great Basin map: Karl Musser, November 17, 2010, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Nüümü irrigation ditches map: Teri Red Owl, “Payahuunadü Water Story,” Wading Through the Past: Infrastructure, Indigeneity & the Western Water Archives, edited by Char Miller, 2021, Claremont Colleges Library.

Alabama Gates photograph: William Detrick. Public Domain, 1924, Rich McCutchan Archives via OwensValleyHistory.com.

Patsiata Dust Storm photograph: Brian Russell, GBUAPCD in Kiddoo, 2019. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Effectiveness and Impacts of Dust Control Measures for Owens Lake. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25658.

Chaffey Ranch postcard: Eastern California Museum, 2024.0.10, https://hub.catalogit.app/9821.

Owens Valley Total Pumping graph: Sally Manning, presentation titled “Groundwater Pumping Effects on Native Vegetation in Owens Valley.”

Mitigation Project photograph: Lynn Boulton, “LADWP Mitigation Projects — Are They Done Yet?” June 9, 2024, https://www.sierraclub.org/toiyabe/range-light/blog/2024/06/ladwp-mitigation-projects-are-they-done-yet.

Patsiata Walk photograph: Lauren Kelly, May 2024.